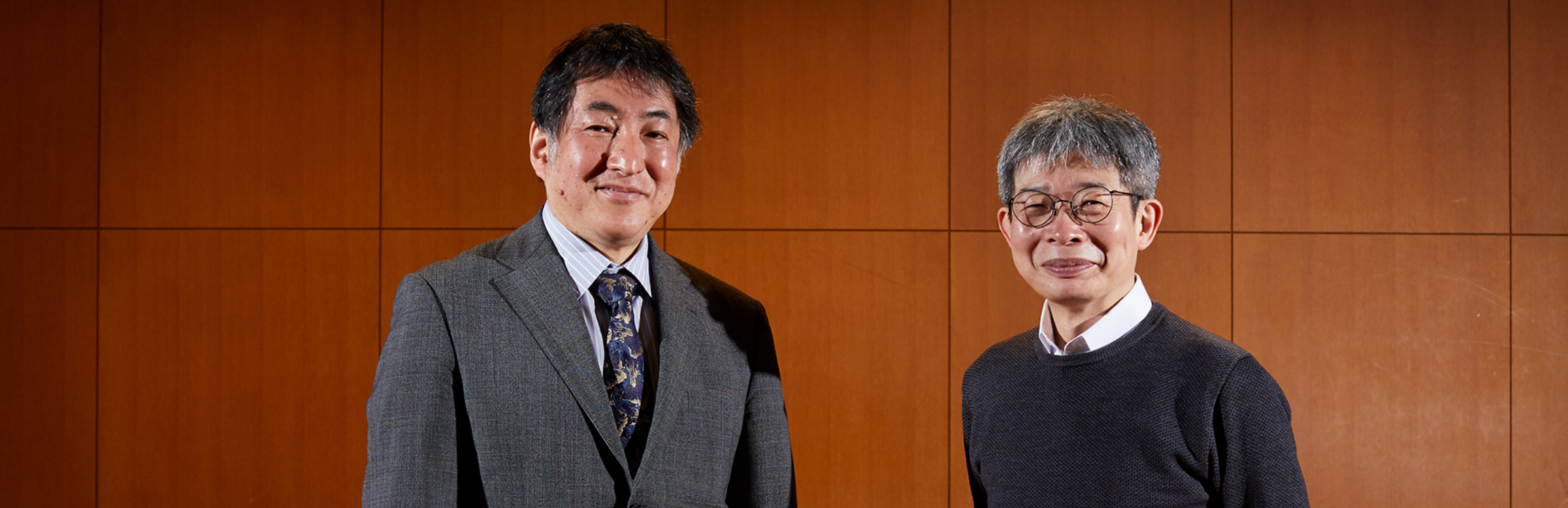

Oriza Hirata wears a variety of professional hats. The playwright and director has received accolades around the world, especially in Japan and France. Also active as an educator, he visited his alma mater towards the end of 2020 to talk with ICU President Shoichiro Iwakiri.

# “Impractical” literature and dramatic arts / #essence of active learning/

#ICU as an experimental lab / #unique community / #COVID-19

“I learned all the vital things in life at ICU: memories of my years here remain indelible.”

Hirata still recalls the words of the then ICU President Hideyasu Nakagawa at his matriculation ceremony about four decades ago: “Most universities teach the practical sciences, but you are here to learn the soft sciences.”

For some time now, Japanese higher education has tended to focus on helping students to acquire the practical skills required to secure employment and build a future career. This trend can be seen, not just in higher education institutions; it can also be attributed to the needs of industry and students, as well as to the structure of Japanese society in which so much emphasis is placed on examination culture.

But what are the competencies required in life? And how do we empower students to reach their potential? The words etched in Hirata’s memory provide clues.

Japan and the world started the year 2021 contending with anxieties regarding a precarious future amidst the coronavirus pandemic and other global issues. In April, Hirata became the President of the Professional College of Arts and Tourism.

In this conversation, the two Presidents, who share specialties in literature and art, delved into the values that ICU brings to society today and how they originated.

INDEX

- 01 The Japanese view of literature and drama as quintessentially impractical is an anomaly in the world The significance of a liberal arts education

- 02The educational value of the dramatic arts Shedding light on the essence of active learning

- 03Carrying out experiments in society: the DNA behind this challenge

- 04Liberal arts, the cornerstone of education at ICU, a unique and inspiring community

- 05Changing patterns of education with COVID-19: Deprived of common space, but granted an online environment

Paragraph 01

The Japanese view of literature and drama as quintessentially impractical is an anomaly in the world

The significance of a liberal arts education

Iwakiri specializes in modern and contemporary French poetry and plays. He has translated numerous French works into Japanese. In 2007, he received the Yuasa Yoshiko Prize for his Japanese translations of Caligula by Albert Camus and L’Alouette by Jean Anouilh, both staged by Yukio Ninagawa.

Hirata is widely known for his Contemporary Colloquial Theater Theory. During his years at ICU, he spent a year in Korea, where he learned to adopt a relativist view while immersing himself in a different culture. He says that this represents the foundation for his theory of drama.

With their keen interest in literature and drama, both men see tremendous potential in these spheres of education.As Iwakiri says, “Art, philosophy and thought are often perceived as not having any practical use; but I disagree. When we think about the meaning of life and how to live your life to the fullest, these can clearly help us.”

Hirata agrees. “It’s unfortunate that, in Japan, drama belongs to a lower echelon in the hierarchy of the arts. Compared to other cultures, Japanese see it in a different light.”

In Japan, the concept of the ‘Arts and Sciences’ may not be very popular as a genre in the classification of academic disciplines. The arts tend to be seen as something to appreciate and to hold in awe as man-made creations, but not as something of practical value. However, such thinking may be an anomaly in the world.

Hirata elaborates, “For example, in the U.S., in a way, drama is placed at the core of liberal arts. Most universities have a drama faculty or department. In Korea, it is regarded as an important component of education. The economic impact of films and drama may have contributed to the dramatic arts being regarded as, in some ways, representative of practical learning.”

So what exactly is the educational significance of genres that belong to the “arts?”

Iwakiri’s reply is based on his vision for improving the quality of education at ICU. “I would like to include these fields as major pillars in our mid- to long-term Plan. Practical skills and techniques are important, but we need to look at why they are necessary and what we want to express by using them. Claiming to pursue the truth or contributing to society without these perspectives is not a healthy approach. The arts, philosophy and thought may not provide immediate and practical solutions, but they are there for us when we need to find direction in our lives.”

Hirata concurs. “Nowadays, people frequently talk about nurturing the ability for problem-solving. But what we need before that is the ability to identify problems. Curiosity and intuition help us discern the things that matter most in our lives. The arts can help tremendously in this regard.”

Paragraph 02

The educational value of the dramatic arts

Shedding light on the essence of active learning

Academic fields in the “arts” nurture the ability to ascertain the essence of a subject and to identify issues. The recent trend in Japanese higher education has been to emphasize the need for self-direction in addition to these abilities. This has led to the promotion of active learning.

In 2014, this approach received attention when it was included in the MEXT Educational Guidelines, referring to active and action-oriented learning, including group discussion and group work, a shift away from the conventional passive style of learning which had represented the norm in Japan.

However, the current situation shows an inclination towards installing learning commons, offering practical training classes, and substantiating opportunities for experience-based learning, which only form part of active learning. What really matters in this approach is dialogue, which ICU has emphasized since its founding days, but which is also closely aligned with the dramatic arts.

Hirata explains, “Drama is a collaborative art form. Individuals act out different characters, but the group needs to incorporate this acting into a single work.”

Iwakiri points out that this experience of diverse people getting together to perform a play resonates with the principle that ICU aspires to: “independent students with diverse values gathering together to form a community.”

Hirata continues, “Many countries include drama in their educational curricula, due to its potential to cultivate self-directed sociability. We tend to lag behind the trend in other nations in the developed world where music, art and drama are offered as compulsory senior high school electives.”

In a town in the U.S., the theater provides a cultural forum and a venue for relaxation, just as the university offers education, and the church a place to share a faith. As Hirata notes, the theatrical arts in Japan may not be held in as high esteem as they are in other parts of the world. They are rarely included in the higher education curriculum as part of the active learning approach, although many universities around the world do so (often with a Faculty of Drama within their organization).

The essence of drama nurtures the mind, self-direction and sociability, which explains what is lacking in Japanese higher education and why the Japanese view of the theatrical arts differs from that in other parts of the world.

Seinendan Performance『Tokyo Note: International Version』

(Photo by Tsukasa Aoki)

Paragraph 03

Carrying out experiments in society:

the DNA behind this challenge

Taking on challenges is another thing these two men have in common.

In April 2021, Hirata became President of the newly established Professional College of Arts and Tourism, located in Toyooka City in Hyogo Prefecture. He also serves as cultural consultant to the City, which emphasizes education, tourism, and the dramatic arts, with aspirations of becoming an international city of dramatic arts.

He notes, “Toyooka City has a population of 80,000, similar to the size of Avignon (with 90,000) and Cannes, a city famous for its film festival, with 70,000. This size makes them an ideal location for cinema and theater performances. Daytime sporting facilities and evening entertainment facilities are prerequisites for an international resort. Toyooka has all the makings of a tourist attraction, with Kinosaki Spa in the vicinity and artistic elements such as the Ebara Riverside Theatre that I built”.

He goes on to emphasize his vision of an education dedicated to the cultivation of knowledgeable personnel for the tourism industry. “Liberal arts is the very essence of tourism education. People need to be armed, not just with the history and social background of the place to which they welcome guests, but also with a breadth of knowledge that forms the foundation of the hospitality they deliver.”

Iwakiri lays out his view of liberal arts, the main pillar of education at ICU, as intrinsic to the university’s steadfast commitment to the establishment of peace in the world for more than 65 years. “My image of liberal arts is that of a multi-stringed instrument that produces a rich harmony expressing an individual’s life – with the various strings representing the diversity of knowledge. The rich harmony reflects the multi-faceted experiences accumulated in life.”

He goes on to say that ICU is committed to the social implementation of the Liberal Arts. “Japanese higher education institutions tend to lay emphasis on skills and technology; but perhaps we need to prepare for an increasingly ageing society, with more and more centenarians, by sharing the liberal arts values and ways of thinking with broader society as “the requisite food for life”. This would include dialogue and critical thinking, values that are emphasized at ICU, but lacking in Japanese society. It’s like a social experiment that homes in on our educational system and ways of thinking, thereby serving as a role model for dissemination into wider society.”

In light of this uniqueness, ICU is often likened to a laboratory. Experiments continue to this day, with alumni, including Hirata, inheriting the DNA that embraces new challenges.

Paragraph 04

Liberal arts, the cornerstone of education at ICU,

a unique and inspiring community

Where does this DNA originate? The answer is that it is rooted in the unique community that is ICU. Despite being located in metropolitan Tokyo, a third of the student body and several of the faculty live on the spacious and leafy campus. The campus community, rare in its diversity, is also home to a unique mode of instruction offered in small classes.

Hirata, who is not a Christian, admits that the “C” component at ICU had a profound influence on his life. “When you work in Europe, a basic understanding of the religion is a prerequisite. I’m afraid many Japanese working in the arts are not aware of this.” Iwakiri adds that you also need to understand the spirit of Christianity. “It’s the premise that we are all equal before God that supports the proximity on campus between students and faculty.”

Since the autumn term, he has initiated the Special Lecture Convocation Hour, for which guests are invited to speak on the theme of a Modern Society and Liberal Arts. Mr. Yoshino of Dari K Co., the first speaker in this series, grows cacao beans in Indonesia to manufacture chocolate. His company operates, not on fair-trade arrangements, but makes sure that farms secure adequate income and sell their beans at appropriate prices.

Iwakiri recalls, “After the lecture, Mr. Yoshino was surprised at the reaction: many ICU- related people visited his store or emailed him. He’d had many opportunities to talk about his company, but the reaction after talking at ICU was very different. This may reflect the unique culture here whereby people are inspired to take action when they find something of value that resonates with their ideals.”

Corporate culture is a popular term that expresses the values and atmosphere within a company, but it may be rare to talk about the “culture” of a university. The ICU community has a distinct culture, which cultivates its own DNA inherited through the generations. Iwakiri also mentions the absence of boundaries in learning at ICU. “The university is famous for its liberal arts providing an interdisciplinary experience in learning; but this is rooted in a liberal community that allows for individual freedom.”

The education at ICU has developed into a ground-breaking culture transcending the liberal arts.

Paragraph 05

Changing patterns of education with COVID-19:

Deprived of common space, but granted an online environment

When we think about the future of education, we need to deal with global issues such as infectious diseases. Higher education has been suddenly and deeply impacted by the coronavirus epidemic. ICU was no exception: it was one of the first Japanese universities to shift all classes online in early March 2020.

Before assuming his post as President, Iwakiri was already dealing with the pandemic as a member of the administration. Looking back at his first year in office, he notes, “If we were just exchanging information, working online would do. However, in a university, we do much more. Faculty give advice about senior theses; students take part in club activities; and there is dialogue on the lawn. It’s the experience of sharing space with others that’s important. What scares me most about the coronavirus pandemic is that it deprives us of this common space.”

At this point, Hirata introduces an experience he had working with elementary school students. “An incident at a primary school left a deep impression on me. As part of the ICT program, tablets had been handed out before the pandemic, and students used them all the time. But when it came to online learning, some had trouble using them properly. After some observation, we found that what supported learning was mutual help among peers. A common learning environment where students teach and learn from friends was the key.”

On the other hand, the two men have noticed something in common during the unprecedented pandemic.

Iwakiri says, “Some students actually prefer online classes. After shifting online, we realized that they had felt uncomfortable with face-to-face dialogue in the conventional classroom. It was a good opportunity to observe the advantages and disadvantages of the two methods.”

Hirata agrees, “Some students told me that it was easier to express their opinions online. In a workshop I hold every year, there were times when the participants seemed withdrawn. But this year, I held it for a full three hours online. Students listened with an intensity that made it easier for me to work with the group.”

In January 2021, a State of Emergency was declared again in several major Japanese cities. As this situation will continue for some time, it is safe to say that higher education is at a turning point. The future of ICU will depend on how its community transforms its education to achieve relevance whilst retaining its focus on acquired experience and knowledge.

[Epilogue]

Teaching the soft sciences at ICU

The words imprinted on Hirata’s memory introduced at the beginning of this article give us a glimpse of the critical thinking and creative laboratory that produces new values at ICU. Today, this unique community faces a new challenge, its values tested by the coronavirus pandemic.

Iwakiri suggests that seeking the common good may help us overcome this present calamity by pursuing what is beneficial for society at large rather than for an individual or a single organization. “In pursuing the common good, some will inevitably be disadvantaged in the process or as a result. It will be important to think critically and listen to many voices. Many have been affected adversely by the coronavirus epidemic. In times like these, education that inspires critical thinking and dialogue, such as that offered at ICU, is crucial. I sincerely hope that this type of education will prevail in broader society to cultivate the competences to live a life of purpose in pursuit of the common good in an age of uncertainty.”

Related Contents

Sub Dialogue

Intellectual interaction

Musings about France

French culture, its characteristics and the difference with that of Japan

Drama and literature: Francophiles discuss their views

The French have a distinct way of approaching culture:

a deep-rooted tradition of individuals developing ideas and engaging others with their thoughts

- Hirata:

- After a French director discovered me, I have been blessed with the opportunity to produce a performance at a national theater in France almost every year. What’s interesting about the French is that, compared to other Europeans, they feel it is their job to find talent.

- Iwakiri:

- That sounds very French, as creators of a very sophisticated aesthetic. From the 17th century onwards, French culture had a tremendous influence on the world. For example, it became the norm and standard in 18th century Germany and in the world of the early 20th century. It wasn’t forced on other cultures, just deeply appreciated and disseminated. The French have an instinct as the forebears of culture.

- Hirata:

- French culture had a profound influence on artists like Van Gogh and Picasso, though they were born elsewhere. The French intelligentsia observe culture in relative terms, in “finding value in what is not ours.” A French director who directed my play said, “By performing this piece, we can show that the Japanese have a drama form totally different from ours. It’s a move against the Franco-centric view.”

- Iwakiri:

- That’s an anthropological perspective that finds value in every culture. I first became interested in French literature by reading poems in the language, but I also find great pleasure attending theatrical performances. There was a time when the Minister of the Interior was unexpectedly seated in front of me when I was invited to see a performance in Paris.

- Hirata:

- I see. The way people spend their time after a theatrical performance differs a lot from that in Japan. The French engage in witty repartee in cafés to discuss the play they have just seen. Topics like French colonial policy may also come up in the conversation, but it’s an engrained custom: citizens, Ministers and mayors alike enjoy intellectual arguments.

- Iwakiri:

- This argumentative culture spurs lively discussion after a performance among French theatergoers. The theatrical arts are well-established, and theaters are integral to the community. The disparity with Japan may be due to the work-style environment, which makes it difficult to spare time to go to the theater.

PROFILE

Shoichiro Iwakiri [President]

The President of International Christian University specializes in French literature. He received a doctorate from the Université Paris 7 (DEA). In 2008, he was awarded the 15th Yuasa Yoshiko Prize (Section of Drama Translation) for his Japanese translations of Caligula by Albert Camus and L’Alouette by Jean Anouilh, both staged by Yukio Ninagawa. Prior to becoming President in April 2020, he was Director of the Admissions Center and Dean of the College of Liberal Arts.

Oriza Hirata [Playwright]

Playwright and director. President of the Professional College of Arts and Tourism. Leader of Seinendan, Artistic Director of Ebara Riverside Theater and Komaba Agora Theater. He graduated from International Christian University College of Liberal Arts in 1986. The recipient of the 2011 French Ministry of Culture Chevalier des Arts et des Lettres is acclaimed around the world.

Planning, and Production and Writing :WAVE.LTD