From 2009 onwards, University of Tokyo administrators, including Professor Shunya Yoshimi, have been promoting educational reforms to foster “resilient Todai students.”

Here is a transcript of the dialogue between Professor Yoshimi and ICU President Shoichiro Iwakiri about the raison d'être of universities.

#Liberal arts #Practical wisdom #Colleges #Universities #Imperial Colleges

Universities in the liberal arts tradition:

their mission from a historical perspective

Global change wrought by the pandemic has plunged us further into an increasingly volatile, uncertain, complex and ambiguous (VUCA) age.

In planning for an uncertain future, higher education has also been forced to foster a capacity for change.

So how should universities transform themselves?

Hints for an answer can be found in the history of liberal arts education.

How have universities and their responsibilities developed over time?

In what capacity do universities exist in present-day Japan?

President Iwakiri was a student at the University of Tokyo. Professor Yoshimi, also an alumnus, has taught, explored his specialty and implemented educational reforms at his alma mater, and taught for a while at Harvard University. The two scholars, with their common educational background and perspective as administrators, looked at higher education from the Middles Ages to the modern day to develop an outlook for the future.

Here are key words that came up in their conversation about the whole concept of universities and what makes ICU ‘ICU’.

INDEX

- 01 Freedom in scholarship: its significance for universities in their formative years

- 02The founding of ICU as a liberal arts college, a peerless global standard institution

- 03The college and university, ICU and the University of Tokyo Their similarities and differences

- 04Global-standard liberal arts firmly rooted in the ICU community

- 05Current enthusiasm for a liberal arts education, its universal value

Paragraph 01

Freedom in scholarship: its significance for universities in their formative years

The ‘MEXT Grand Design for Higher Education toward 2040’ Report highlights the importance of nourishing intellectual breadth as have other cultural and educational policies. In recent years, many universities in Japan have introduced liberal arts into their curricula.

As the concept of liberal arts is often misunderstood as referring simply to knowledge in general, the discussion began with Yoshimi commenting that the notions of general and liberal knowledge may contradict each other.

Iwakiri’s reply was that general knowledge can also be expressed as culture, which derives from the concept of ‘cultivation’, an agricultural metaphor related more or less to a particular plot of land. In this sense, the words ‘culture’ and ‘liberal’ differ in that the latter connotes freedom.

Culture defines the customs and traditions rooted in a nation, region and land. It contributes to their development, by providing a foundation. On the other hand, liberal arts, which came into being in an educational setting, originated from freedom in scholarship.

In a medieval European university, the seven liberal arts were: grammar, rhetoric, logic, arithmetic, geometry, music and astronomy, which were in a way established opposite the three disciplines, theology, law and medicine, when universities first arose in the 12th to 13th centuries. Theology served God; the law, the state; and, medicine, the people. These practical disciplines prepared students for specific professions; but liberal arts established value in the act of learning itself, with no particular objective such as attending to the state, the city or an authority.

It is clear then that culture, which is deeply related to the notion of the state and the locality, is not always synonymous with liberal arts, which forms the basis for modern day academic freedom.

Yoshimi:Liberal knowledge in the medieval ages was founded both on a horizontal freedom of movement and a vertical relation with the powers that offered protection from the local authorities. In 12th to 13th century Europe when urban networks were formed, students travelled for months to seek the mentorship of outstanding scholars. Fearing oppression from local political leaders, they sought protection from privileged powers such as the Pope and the Holy Roman Emperor to justify their autonomy. The driving force that sought freedom in the interest of scholarship provided the impetus for shaping the prototype of future universities.

Iwakiri:Freedom is also an important concept in social settings, academia, and intellectual ideas, but I feel it is the most fundamental aspect of liberal arts.

In contemporary Japan, most of us take the academic freedom stipulated in the Constitution for granted. However, in the early days of universities, freedom meant a lot more than it does today. This legacy has been inherited and enhanced in contemporary liberal arts education.

In becoming accustomed to academic freedom as a given in Japan, it may be natural for people to lack basic understanding for this concept and to confuse liberal arts with general knowledge. On the other hand, academic freedom and intellectual breadth have both contributed to the establishment and structure of the modern university, but this has also been the source of constraints in the organization.

Paragraph 02

The founding of ICU as a liberal arts college, a peerless global standard institution

The tradition of liberal arts at the core of the education at ICU lays emphasis on the learning endeavor itself in pursuing whole-person development and maturity of the personality. In this paragraph, the two scholars highlight the characteristics of ICU as a liberal arts college.

Yoshimi:ICU was founded immediately after Japan’s defeat in World War II, in an attempt to introduce an American-style, liberal arts college in occupied Japan. I think the educational model of elite American colleges was directly imported in a good sense.

Iwakiri:I agree. With deep regret for the circumstances that led to World War II, ICU sought to cultivate personnel to establish peace in the world. Its unique genesis laid the foundation for an unprecedented proving ground for creating a unique community in Japan.

With approximately 3000 students and 150 full-time faculty, its student-teacher ratio is on a par with global standard liberal arts colleges. There is active interaction among students and with faculty. This kind of emphasis on dialogue, an essential element in liberal arts, may not be possible at larger institutions with more students.

Yoshimi:The characteristics of a university are formed in the way in which different paradigms are combined. ICU has been very tactful in this regard.

Iwakiri: I would like our students to cultivate perspectives in the humanities, social sciences and natural sciences simultaneously when they study liberal arts.

This is not simply a matter of studying across the arts and sciences. It is a process of absorbing ways to approach humankind and the world that work in harmony. This includes developing perspectives in a social context and from a scientific view, as well as for the creative process in irreproducible works of art, all of which are crucial for students to understand the human condition and to connect with the larger world.

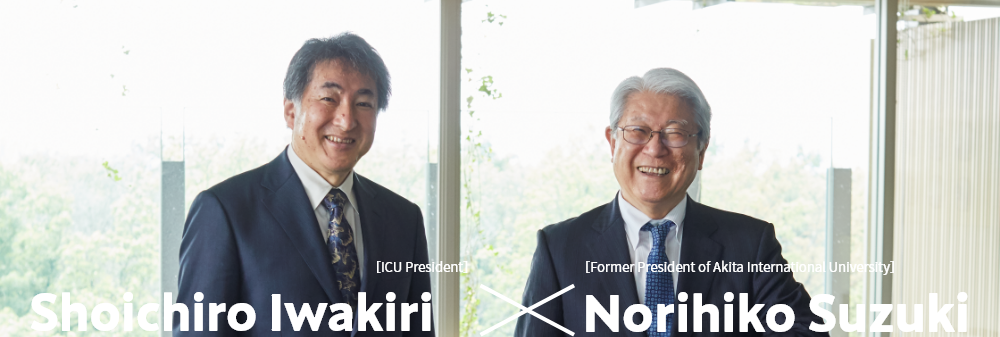

Yoshimi:My impression of ICU since the days of President Norihiko Suzuki is that it has been very audacious in introducing the major/minor and double major system. These arrangements are the norm worldwide, especially at American universities, but not in Japan. This shows that ICU is blazing the trail as the domestic front-runner in higher education.

We should perhaps talk of multi-faceted learning rather than that across the arts and sciences. Disparate disciplines co-exist and provide deeper academic perspectives that work together to intensify and diversify our views. It’s important to combine horizontal and vertical learning.

The major system provides the foundation for interdisciplinary multifaceted learning. ICU offers 31 majors with major/minor and double major arrangements that allow for a very flexible combination of fields for students to pursue. The Center for Teaching and Learning provides academic support in designing multifaceted programs of study. This is the unique characteristic of the liberal arts system established at ICU that differentiates it from other Japanese universities.

Paragraph 03

The college and university, ICU and the University of Tokyo Their similarities and differences

The previous paragraph delved into those aspects of ICU as a college that implements a liberal arts education. In general, a university usually has several faculties that offer students a wide variety of disciplines to choose from. ICU has a single college of liberal arts, but offers a wide range of subjects to study.

An emblematic university in Japan would arguably be the University of Tokyo. Despite different pathways taken by the two institutions over the years, a connection can be traced back to the founding days of ICU in the aftermath of World War II.

Even before the basic plan for the establishment of ICU was resolved on June 15, 1949, at the Gotemba Conference, records show that Shigeru Nambara, the last prewar President of the Imperial University of Tokyo and Tadao Yanaihara, his successor and first postwar President, contributed to the thinking behind the foundation of ICU. In fact, Yanaihara delivered a congratulatory message at the Dedication Ceremony of Establishment in 1953. Yoshimi points out that this reflected a problem they saw within their University.

Yoshimi::The Imperial University of Tokyo had a rigid, faculty-centered structure, as it adopted the Western model during the Meiji Era when it was established. For example, the Faculty of Medicine emulated the German system; the Faculty of Engineering, the Scottish system; the Faculty of Law, the French system; and, the Faculty of Agriculture, the American system. This was an attempt to absorb the best of cutting-edge Western intelligence in the most efficient way possible.

This is how a firm vertical structure was put in place, with emphasis on the autonomy of each faculty rather than academic freedom, and this became the model for larger universities in Japan.

How did ICU come into being as a liberal arts college under the strong influence of the American Occupation? It was perhaps envisioned as a way to overcome the disconnect between faculties at Imperial Universities, which had been a problem from the Meiji era.

The American liberal arts model adopted at ICU perhaps materialized from a sense of crisis felt at the time, for the lack of horizontal integration in learning across disciplines.

In the academic world, globalization and horizontal integration will proceed further. Yoshimi warns that Japanese universities may not be able to ensure their continued relevance, if they cannot expand their outlook beyond the walls of their own institutions in conferring degrees. Both ICU and the University of Tokyo acknowledge the importance of liberal arts though they differ in institutional structure and approach. It may be notable that both are seeking to break down silos in the organizational structure. At ICU, cross-unit activity is not hampered by walls, as it sustains a truly liberal community.

Paragraph 04

Global-standard liberal arts firmly rooted in the ICU community

Issues in higher education in Japan are not limited to vertical segmentation. Another problem is the prevalence of the lecture-centered approach in the classroom, modeled after the tradition at Imperial Universities. The number of subjects students take in the curriculum also corroborates this fact.

In a survey conducted by the National Institute for Educational Policy Research in March 2016, first-year through third-year students took 10-14 courses during the half-year term, which amounts to taking courses in 4 different subjects a day. This makes it difficult to concentrate on each subject and for knowledge to sink in.

Yoshimi:When you try to impart an all-inclusive body of knowledge, the volume is so immense that the priority for the instructor becomes merely imparting the necessary elements rather than taking a learner-centered approach. This is probably the most problematic issue in Japan.

Iwakiri::At ICU, we limit the number of courses students take per term. They typically meet for a course three times a week, on Mondays, Wednesdays and Fridays, and take about 4-5 courses per term.

Yoshimi:We should all emulate the ICU model, which reflects the approach most universities take around the world. When students take 4-5 courses per term, they can concentrate more on each subject. They will probably work harder because failing a course can affect their graduation timeline. Students see their instructor and fellow classmates several times a week. It’s a shift from all-inclusive to deeper instruction in small numbers. This is essentially what the learning experience at university should be.

The language barrier is another serious problem when considering whether Japanese universities satisfy global standards.

For example, compared to Korean students, who have been studying English in elementary school as a compulsory subject at a much earlier stage than in Japan, and Chinese students, who are always eager to study abroad, their Japanese peers display inadequate skills in languages other than their mother tongue. The pandemic has further aggravated the situation, with a strong reluctance to study abroad.

Yoshimi said, “ICU students are more than enthusiastic about studying abroad. That stands out among Japanese universities even though this is common in most places in the world. This is invaluable when we think about the reluctance of Japanese students to study abroad.”

Various measures exist as solutions for this problem, such as introducing bilingualism (as at ICU), multilingualism, international dormitories (a recent trend) and COIL education. But these strategies will not suffice when adopted superficially in the education system, to solve issues at the core of the problem.

These problems need to be addressed by thinking about the future of universities as mentioned at the beginning of this article.

Paragraph 05

Current enthusiasm for a liberal arts education, its universal value

ICU offers a bilingual education with flexible major arrangements, characteristics common to universities around the world. In the last paragraph, the two delved into what makes ICU ‘ICU’.

As mentioned at the beginning of this article, due to re-acknowledgement of the importance of liberal arts education in recent years, many other universities in Japan have incorporated the tradition in their programs.

Iwakiri:We have many more liberal arts universities in Japan. That in itself is a good thing: something of value is being adopted widely. I see it as an effort to spread the tradition together, rather than us losing our edge or being caught up with.

Yoshimi: I agree. The world sees the education at ICU as standard practice, as liberal arts was the basis of higher education. In its long history, specialized education was not the only objective of instruction: an institution that does not offer a liberal arts program would be considered a vocational school, rather than a university. Even vocational schools now emphasize the importance of liberal arts. That brings us to the fact that scholastic endeavor needs freedom or leeway for the inquisitive individual to move in a liberal environment.

Iwakiri:The college of arts and sciences at other universities is often placed as an administrative unit along with faculties of law or economics, but ICU has a single college of liberal arts, with specialized majors in the curriculum. This is a big difference that I usually ask applicants and their parents to understand.

Yoshimi:It’s the faculty as opposed to the college. Historically, faculties and colleges were disparate organizational units in academia, so there is a contradiction in establishing a college of arts and sciences on an equal footing with faculties. The college provides a bridge across disparate disciplines and faculties. The idea of liberal arts holding the whole university together, is now spreading among medium-sized universities in Japan.

Iwakiri:I hear quite often that ICU alumni who go on to graduate schools have a difficult time in their first year because they lack some of the specialized knowledge that their classmates had absorbed in their undergraduate years. We do admit that to be a weakness of our system, but from their second year onwards, they do as well as their peers from other colleges. They possess a potential that accelerates growth after they catch up, a result of the instruction in liberal arts that unifies the educational landscape at ICU.

Yoshimi:That students lack some knowledge is not a problem, as long as they are thoroughly trained in basic thinking and debating skills. Those are the very competencies Japanese universities need to empower students with.

The liberal arts education at ICU does not aim to impart an all-inclusive body of knowledge. The emphasis is on nurturing multilateral perspectives and basic indispensable skills such as critical thinking and debate, to cultivate the ability for lifelong learning. The education has a universal value on a par with universities around the world to cultivate the skills for a well-lived life in a global society.

What makes ICU ‘ICU’ is simply the community and the distinct culture on campus. As Yoshimi tells us, it is the particular culture on a par with that of the world with the whole university committed to liberal arts. That is at the root of ICU’s education.

[To conclude]

The mission of a university created in the liberal arts style――

The two men’s multi-tiered dialogue provided various clues to the query posed at the beginning of the conversation.

Liberal arts is often confused with general knowledge, with universities introducing the tradition in their programs without a deep understanding of the difference between the two. Does freedom that lies at the base of liberal arts really exist in that type of setting? Can universities siloed by disciplines break away from an education that crams knowledge into students?

We have reasons for optimism. Many universities have striven to implement reforms and flourished after World War II. We need to create a model for reform in a new era.

ICU is an eternal experimental ground as the ‘University of Tomorrow’. It has established an educational system which continues to evolve. The 2021-2025 Medium-term Plan developed under the leadership of President Iwakiri adopts the slogan, “Social Implementation of Liberal Arts,” to promote awareness of the tradition in society.

As Iwakiri suggests, ICU will take the lead in spreading the liberal arts model for universities planning their future, by expanding the tradition together, as the University of Tomorrow, for all in the field of education.

Related Information

Sub Dialogue

Intellectual Interaction

Converging Expertise on Class Management

During the conversation, the two introduced new approaches to learning with abundant examples. Here are some ideas they mentioned that could not be included in the transcript.

- Iwakiri

- Proust wrote the following: “Some name, read long ago in a book, contains among its syllables the strong wind and bright sunlight of the day when we were reading it.” I feel it’s important to take in what you learn with the surrounding environment when you absorb something new. This can be difficult when the instruction is offered online, but I still want to make sure students have this experience.

- Yoshimi

- Talking about online instruction, Minerva University is an interesting example. It does not have a campus, and students take courses online. However, it is not an online university. This is the important part: students move to and from the university’s dormitories in 7 cities around the world. The world is their campus. They experience all sorts of hardship when they travel and stay in these cities. Simply adopting online means for instruction could be destructive for universities in the post-coronavirus age.

- Iwakiri

- When shifting to online delivery, the student-teacher ratio is important. In the case of ICU, with many small sized seminar-type classes, it was perhaps easier to change over to online instruction.

Courses on demand may need to go through a series of revisions to have a meaningful effect on student learning. But increasing their number will be a problem for universities. A shift to small classes will be a prerequisite for online courses. On the other hand, it will expand the potential for learning, as we can offer those who cannot come to the campus, for whatever reason, another means to learn.

Professor Yoshimi, you also taught at Harvard University. Is there anything you’d like to mention about class management there?

- Yoshimi

- Professors are not always indispensable in education, but good TAs are. Reliable TAs whom students feel close to, can enhance the intensity of a discussion.

- Iwakiri

- It’s the idea of team teaching. I would like to adopt that at ICU.

- Yoshimi

- In Europe, you have a system that allows students to move to and from universities. That’s also interesting.

PROFILE

Shoichiro Iwakiri

The President of International Christian University specializes in French literature. He received a doctorate from the Université Paris 7 (DEA). In 2008, he was awarded the 15th Yuasa Yoshiko Prize (Section of Drama Translation) for his Japanese translations of Caligula by Albert Camus and L’Alouette by Jean Anouilh. Prior to becoming President in April 2020, he was Director of the Admissions Center and Dean of the College of Liberal Arts.

Shunya Yoshimi

University of Tokyo Graduate School of Interdisciplinary Information Studies Professor Shunya Yoshimi specializes in sociology, culture and media studies. Prior to assuming his present post in 2004, he was a research assistant and assistant professor at the University of Tokyo Institute of Journalism and Communication Studies, and Professor at the University of Tokyo Institute of Socio-information and Communication Studies. He was also Chairman of the Board of Trustees of the University of Tokyo Newspaper and University of Tokyo Press.

Planning, and Production and Writing :WAVE.LTD